A Brief Review of the Pentateuch

“The Pentateuch” is the Greek name given to the first five books of the Old Testament, the books that the ancient Hebrews called “The Law” (or, “The Torah.”) The Hebrew word “Torah” means “instruction,” a term well suited to describe these five books since they contain both the historical as well as the legal foundation of the Old Testament covenant.

The first of the five books, Genesis, deals with the creation of the world and man’s God-given place in it, the primeval history of the human race, and then focuses on the history of the Old Testament patriarchs: Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. Genesis records God’s call to Abram to leave his homeland, Ur of the Chaldeans, and journey to the Promised Land of Canaan, and the divine promise that Abram will become the father of a great nation–a nation that will live in covenant with God, dwelling in His land and being His unique possession. As a token and assurance of the Lord’s commitment to His promise, He give to Abram the new name, “Abraham,” a name meaning, “father of a multitude” (Genesis 17:5.) The Book of Genesis concludes with the embryonic covenant nation (consisting of Jacob, who has been re-named “Israel,” and his twelve sons together with their families) journeying down into Egypt.

As the Book of Exodus opens we find that the embryonic covenant nation, by the blessing of the Lord, has grown into a great multitude, so much so that it has become a threat to the world-power of that day, the empire of Egypt (Ex. 1:7-10.) As its title suggests, the Book of Exodus records the Lord’s miraculous deliverance of His people from their Egyptian oppressors via their safe passage through the parted waters of the Red Sea. Under the leadership of their divinely appointed redeemer, Moses, and by means of the Lord’s own visible presence (in the pillar of cloud and fire), the Israelites are brought to Mt. Sinai, the mountain of God. There the Lord, true to His original covenant with Abraham (Gen. 15), enters into covenant with the nation of Israel, claiming them as His own possession and pledging to be their God. The Book of Exodus climaxes with the covenant nation dwelling in the presence of the Lord at the foot of Mt. Sinai with the Lord’s very throne in their midst (in the form of the sacred ark of the covenant housed in the tabernacle, Ex. 40:34.) But the divine promise made to Abraham that his descendants would possess the Promised Land of Canaan was yet to be fulfilled. Hence, the Book of Exodus concludes with the testimony that, by means of the pillar of cloud and fire, the Lord led His people “through all their journeys” (Ex. 40:38.)

The journey from Mt. Sinai, through the wilderness, to the border of Canaan is narrated in the fourth book of the Pentateuch, the Book of Numbers. Inserted between Exodus and Numbers is the Book of Leviticus. This third book of the Pentateuch contains the detailed prescriptions for the nation’s worship of the Lord and fellowship with Him by means of the various sacrifices He ordained. The book also contains sundry laws and regulations to govern the nation’s conduct as the redeemed people lived in community with their God and with one another. As the nation stands at the brink of the Jordan River and prepares to enter the Promised Land of Canaan, the faithfulness of the Lord their God is re-iterated and the covenant is formally renewed in the fifth book of the Pentateuch, the Book of Deuteronomy.

Thus, in the words of W.A. Elwell (p. 3), “The Pentateuch forms the historical, religious, and theological basis for the entire course of Hebrew history.” The human authorship of these five books down through the ages has been attributed to none other than the divinely appointed redeemer of God’s Old Testament people, Moses. By way of example, the Rabbis understood the words of Deuteronomy 31:9 (“And Moses wrote this law”) and 31:24 as referring to the whole Torah (Gen. 1:1 through Deut. 34:12.) They only differed in opinion as to whether Moses wrote the whole work at once after his last address, or whether he composed the earlier books gradually, and then completed the whole by writing Deuteronomy and appending it to the previous four books (C.F. Keil, pp. 25-26.) Keil’s reference to the opinion of the Rabbis shows their belief in the Mosaic authorship of the entire Pentateuch. However, Deuteronomy 31:9 and 24 seem to be referring explicitly to the renewal of the covenant as contained in that fifth book of the Pentateuch. Nevertheless, the tradition of the Mosaic authorship of the entire Torah (“The Book of the Law”) is affirmed by the New Testament (note, for example, Lk. 24:44; Jn. 1:45; 7:19; Acts 15:21.)

The Book of Exodus

Authorship/Content/Theme

Moses was especially suited to write the Book of Exodus, (as well as all the rest of the Pentateuch.) Scripture asserts that Moses was raised by one of Pharaoh’s daughters (Ex. 2:10.) According to R.K. Harrison (p. 575), it has been discovered that in the New Kingdom period of Egyptian history there were numerous royal residences and harims in various parts of Egypt, including the eastern Delta region in the vicinity of Goshen, where ladies of noble birth resided along with royal concubines. Children of the harim, especially male princes, were frequently educated under the supervision of the harim overseer. At a later stage the princes were placed in the care of tutors who saw to it that their charges were educated by the priestly caste in reading and writing. (Note: In light of what Acts 7:22 tells us about Moses’ education, what Harrison informs us about the New Kingdom age of Egyptian history was in some way also the practice at the time of Moses’ youth, which seems to have been at an earlier period of Egyptian history.)

The name of this second book of the Pentateuch, “Exodus,” is the name by which it was designated in the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Old Testament.) The name, of course, is highlighting that great event in the book by which the Lord miraculously brought His people out of their Egyptian bondage in order to bring them into covenant with Himself as His own holy possession. The very first verse of Exodus (“And these are the names of the sons of Israel who came into Egypt”) serves to connect this book with the first book of the Pentateuch. This is evident from the use of the conjunction “and.” Furthermore, this opening verse of Exodus is repeating the statement made in Genesis 46:8. The concluding episode in Genesis (50:22-26) also highlights the connection between these two books: At the time of his death, Joseph requested that his bones be carried up from Egypt. When Israel finally left Egypt, the text (Ex. 13:19) makes mention that Moses took the bones of Joseph (R. Dillard and T. Longman, p. 57.)

The content of the book may be outlined according to a number of differing schemes suggested by a variety of commentators; but perhaps that suggested by C.F. Keil most faithfully represents the overarching theme of the book. Keil reminds us that the 430 years of the sojourn of the Israelites in Egypt was the period during which the immigrant family was to increase and multiply under the blessing of God until it had grown into a nation and was ripe for the covenant the Lord had initially made with Abraham. Now, after this interval of some 400 years, the next stage in the execution of the divine plan of salvation is about to commence with the call of Moses and the establishing of the kingdom of God in Israel. To this end (1) Israel was liberated from the power of Egypt and (2) was brought into covenant with the Lord to be the people of His possession. According to Keil, these two great facts form the kernel and essential substance of the book (C.F. Keil, The Pentateuch, Vol. 1, p. 416.)

Operating from this perspective, Keil sees the Book of Exodus as being divided into two distinct parts, each consisting of seven sections. The first part (chapters 1:1 through 15:21), is composed of the following sections: (i) the preparation for the saving work of God through the multiplication of Israel into a great people, their oppression in Egypt (stimulating their desire for deliverance), and the birth of their liberator (chap. 1-2); (ii) the call and training of Moses to be the deliverer and leader of Israel (chap. 3-4); (iii) the mission of Moses to Pharaoh (chap. 5:1-7:7); (iv) the negotiations between Moses and Pharaoh concerning the emancipation of Israel (chap. 7:8-11); (v) the consecration of Israel as the covenant nation through the institution of the Passover (chap. 12:1-28); (vi) the Exodus brought about as a result of the tenth plague, the slaying of all the Egyptian first born (chap. 12:29-13:16); and (vii) the passage of Israel through the miraculously parted waters of the Red Sea, the destruction of Pharaoh’s army, and the subsequent song of triumph (chap. 13:17-15:21.) The second part of the book (chapters 15:22 through 40:38), according to Keil, is composed of the following sections: (i) Israel’s march to the mountain of God (chap. 15:22-17:7); (ii) the attitude of the Gentile world toward Israel as seen in the hostility of Amalek on the one hand and the testimony of faith made by Jethro the Midianite on the other (chap. 17:8-18:27); (iii) the establishment of the covenant at Sinai, with all of its promises and requirements (chap. 19:1-24:11); (iv) the divine directions with regard to the erection and arrangement of the Lord’s earthly dwelling place (chap. 24:12-31:18); (v) Israel’s apostasy in the form of making the golden calf and their subsequent restoration through the intercessory work of Moses (chap. 32-34); (vi) the construction of the tabernacle in preparation for the Lord’s coming to dwell in the midst of His people (chap. 35-39); and (vii) the setting up of the tabernacle, its solemn dedication, and the coming of the Lord to dwell among His people (chap. 40) (C.F. Keil, The Pentateuch, Vol. 1, pp. 416-417.)

The Date of Exodus

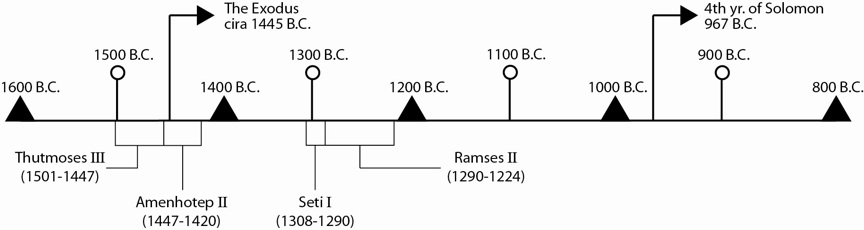

The “early” date for the Exodus would place the event in the fifteenth century B.C. and see Moses leading the people out of Egypt during the reign of Amenhotep II (1447-1420 B.C.) The Scripture passage of 1 Kings 6:1 seems to support this “early” date. That passage states, “In the four hundred and eightieth year after the Israelites had come out of Egypt, in the fourth year of Solomon’s reign over Israel…he began to build the temple of the LORD.” With relative certainty, scholars are able to identify the year 967 B.C. as the fourth year of Solomon’s reign. Going back 480 years prior to this date would place the Exodus in the year 1447 B.C. (or thereabout, allowing for the possibility that 480 is a rounded-off number.) As stated above, this would mean that the Exodus occurred during the reign of Amenhotep II (1447-1420 B.C.)

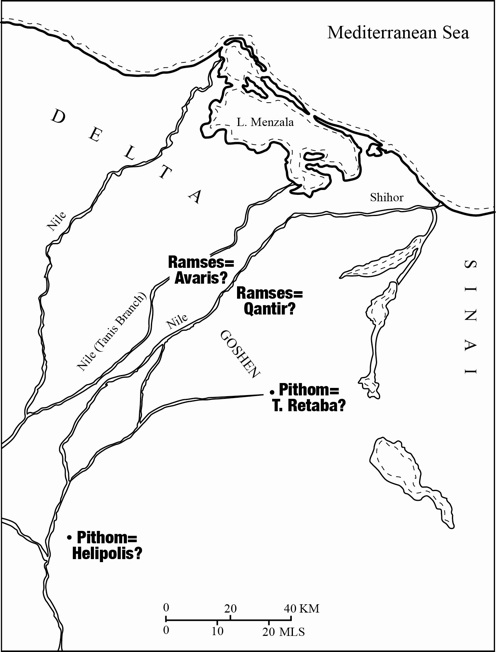

However, those scholars who support a “later” date (thirteenth century B.C.) for the Exodus rest their theories in part upon the reference in Exodus 1:11. That passage implies that the Hebrews were in bondage when the store cities of Pithom and Ramses were being rebuilt. Archaeological excavations seem to suggest that those cities were rebuilt in the thirteenth century B.C, during the reign of Seti I (1308-1290 B.C.) This would make Seti I the Pharaoh of the oppression and Ramses II (1290-1224 B.C.) the Pharaoh at the time of the Exodus. (For further clarification, the student is referred to the accompanying time line.)

Excavations at the site of Avaris (see map below) revealed the reconstruction of the city under Seti I. (Note: Avaris was the old Hyksos capitol in the Nile Delta. At a later date the city was renamed the “House of Ramses” and bore this designation from ca. 1300-1100 B.C., R.K. Harrison, p. 322.) Furthermore, stelae (statues) and other artifacts bearing the names of Ramses II and his successors were also found at this site.

According to R.K. Harrison (p. 322,) another ancient site, Tell el-Retabeh (or, T. Retaba,) is now known to have been Pithom. Work at this site has uncovered some of the massive brickwork erected in the time of Ramses II. Since no trace of Eighteenth Dynasty (the fifteenth century B.C. Pharaohs Thutmose III and Amenhotep II ruled during the Eighteenth Dynasty) construction is evident at the site, it appears that the Exodus tradition of Hebrew forced labor is referring to the days of Ramses II.

But those scholars who hold to the “early” (fifteenth century B.C.) date for the Exodus dispute the identification of the city of Ramses with the excavation site at Avaris. J.J. Bimson (quoted by R. Dillard and T. Longman, p. 60) states that contemporary scholarship substantially favors Qantir as the site of the ancient store city of Ramses. Qantir, unlike Avaris, does show evidence of earlier occupation that allows for a fifteenth century B.C. date for the site.

Bimson concedes that Pithom may be identified with Tell el-Retebah (a.k.a.; T. Retaba;) but, then again, it may be identified with Heliopolis. In either case, in contradistinction to Harrison, Bimson maintains that both these sites show signs of having a history that goes back earlier than the thirteenth century B.C. (R. Dillard and T. Longman, p. 60.)

Note: One might inquire why the Book of Exodus identifies these cities by the names “Ramses” and “Pithom,” if, indeed, they were not called by these names until well after the Exodus. Dillard (p. 60) replies to this by suggesting that the names could be the result of a later textual updating. By way of a more contemporary example, in speaking of American history, we may refer to the Dutch colonizing New York, when in fact they called it “New Amsterdam.” It was only when the British took over that it was renamed “New York.”

All these scholars note the tentative nature of the conclusions to be drawn from archaeological discoveries. In the words of Dillard and Longman: The archaeological arguments that some take to lead inexorably toward a late (thirteenth century B.C.) date of the Exodus are questionable or wrong… Archaeological results…are not brute facts with which the biblical material must conform and that can prove or disprove the Bible. Archaeology rather produces evidence that, like the Bible, must be interpreted (p. 61.)

When we consider all the data, the weight of the evidence seems to be in favor of the “early” date for the Exodus. G. Archer contends that no other known Pharaoh besides Thutmose III (1501-1447 B.C.) fills all the specifications for being the Pharaoh of the oppression (with his son, Amenotep II, being the Pharaoh at the time of the Exodus.) Thutmose III alone was on the throne long enough to have been reigning at the time of Moses’ flight from Egypt, and to have died not long before Moses’ call at the burning bush. He was ambitious and energetic, and engaged in numerous building projects for which he used a large slave-labor task force. His son, Amenotep II, seems to have suffered some serious reverse in his military resources, for he was unable to carry out any invasions or extensive military operations for some time after the initial years of his reign. This relative feebleness of his war effort (by comparison with that of his father) would well accord with a catastrophic loss of his chariotry in the waters of the Red Sea (G. Archer, pp. 217-218.)

Finally, in further confirmation of Amenhotep II as the “Pharaoh of the Exodus,” there is the “Dream Stela” of Thutmose IV (1421-1412 B.C.) In the text on this stela the god Horus appears to young Thutmose in a dream and promises him the throne of Egypt if he will remove the sand from the Sphinx. If Thutmose IV had been the oldest son of Amenhotep II, there would have been no reason for a divine promise that he would become king. He would naturally have succeeded his father to the throne. It is a necessary inference, therefore, that the oldest son of Amenhotep II must have preceded his father in death. This well accords with the record in Exodus 12:29 that the eldest son of Pharaoh died at the time of the tenth plague (G. Archer, p. 218.)

Bibliography

Archer, Gleason L. Jr.; A Survey of Old Testament Introduction; Moody Press, Chicago, 1964 (Sixth Printing, 1970.)

Connell, J.C.; “Exodus,” The New Bible Commentary, Edited by Prof. F. Davidson; The Inter-Varsity Fellowship, London, 1953 (Reprinted, October 1967.)

Dillard, Raymond and Tremper Longman III; An Introduction to the Old Testament; Zondervan Publishing House, Grand Rapids MI, 1994.

Elwell, Walter A.; “The Pentateuch,” Evangelical Commentary on the Bible, Edited by W.A. Elwell; Baker Book House, Grand Rapids MI, 1989.

Harrison, R.K.; Introduction to the Old Testament; Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., Grand Rapids MI, 1969 (Fifth printing, November 1975.)

Hoffmeier, James K.; “Exodus,” Evangelical Commentary on the Bible, Edited by W.A. Elwell; Baker Book House, Grand Rapids MI, 1989.

Keil, C.F.; Biblical Commentary on the Old Testament, The Pentateuch, Vol. 1; Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., Grand Rapids MI, Reprinted, February 1971.

Young, Edward J.; An Introduction to the Old Testament; Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., Grand Rapids MI, 1949 (Fourth Printing, June 1969.)